OFFERINGS TO THE POTOMAC: ACKNOWLEDGING INDIGENOUS PLACE

/Upcoming Events

OFFERINGS TO THE POTOMAC

ACKNOWLEDGING INDIGENOUS PLACE

February 24 - December 15, 2025

Buchanan Hall Atrium Gallery

Curated by Dr. Gabrielle Tayac and Public History in Action students

Co-Curated and Designed by Mason Exhibitions

In Indigenous tradition, when we enter another people’s territory, we make heartfelt offerings to honor their lands and community. We invite you to envision yourselves as part of a story that is much older than George Mason University, even older than Fairfax. The Doeg Tribe lived in a major village along the Potomac River called Tauxenent (Tauj-ah-nahnt) near the place where we now stand. In the late 1600’s, the colonial Virginia militia attempted to erase the Doeg people through warfare and removal. Many perished in violence and enslavement in the West Indies. But Doeg descendants remain in the region; some are in current Piscataway and Rappahannock tribes and others trace their ancestry back through individual family lines.

We welcome you to consider ways to honor the ancestors, join in caring for these lands in right relationship, and support contemporary local Indigenous communities. This is an Indigenous place. Home is here.

Mason Exhibitions is honored to expand the offerings to include student and alumni artwork by CJ Davis, Girasol O’Neill, Ayman Rashid, and students taking Intro to Darkroom with Stephanie Benassi in Fall 2024.

Offerings to the Potomac presents three major Indigenous communities in Northern Virginia:

Local Intertribal Community – Native Americans from across the United States and Canada live and work in this region. The American Indian Society of Washington, D.C. works to gather community for cultural, spiritual, educational, and social support. The Piscataway (Maryland) and Rappahannock (Virginia) tribes have lived on these lands for millennia.

Mayan Nation – There is a large diasporic Central American Indigenous population in this area. The International Mayan League is an important organization representing a rapidly growing community.

Andean Indigenous Community – Longer established in Northern Virginia, Quechua and Aymara speakers from Andean countries are a dynamic part of this region’s culture.

Mason Students and Alumni – For this exhibit, current students and alumni engaged creatively with culture, land, and community to create contributions, “offerings” to the Potomac.

Special Thanks to Collaborators, Sponsors, and Supporters

This exhibition grew out of the “IndigenoUs Northern Virginia: Activating Local and Diasporic Native Identities at Mason” project of Dr. Alison Landsberg and Dr. Gabrielle Tayac, funded by Mason’s Anti-Racism and Inclusive Excellence (ARIE) grant awarded to the Center for Humanities Research (CHR) and the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (RRCHNM) in February 2023.

“Indigenous Northern Virginia” began with a Summer Research Institute of students who connected with diverse indigenous communities in NOVA through experiential listening and dialogue. Learn more about the Summer Institute in 2023 and related programming. Learn more about the Summer Institute in 2024.

Co Creative History Space: https://cocreativehistoryspace.wordpress.com/about/

Contemporary Indigenous Peoples on Ancestral Lands

Nana Xhiv (Maya Ixil)

Survivor of the Ixil Genocide

“Niños, jóvenes y mujeres, canten, dailen, griten, amén y sean libres porque oramos y llevantamos nuestra bandera de lucha por su bien y libertad.”

“Children, young people, and women, sing, dance, shout, love, and be free because we pray and raise our flag of struggle for your good and freedom.”

Joe Gaines (Choctaw) playing drum in Washington, DC

The Gray Family (Rappahannock, Piscataway) at the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC 2023

Chakana Marcela Ardaya (Quechua), a special education teacher, Mason alumna, and herbalist, joyfully blesses a Piscataway ceremonial tobacco field, August 2024. Courtesy of Chakana Ardaya.

INSTALLATION VIEWS

Featured Objects

The Land has Memory, 2024

On loan from Tamara Carter and Joe Gaines (Choctaw)

Eagle Feather (VA), Canvas, Beads, Tobacco, Sage, Cloth

This installation was made in dedication to the Doeg so graciously by the efforts of Joe Gaines and his wife Tamara Carter with the photography of Toni Kinsley. It was done to acknowledge that while the Doeg as a people are no longer with us, there are descendants living today. We not only strive to remember them but teach others about them to honor them and their pain. The eagle photos and feathers as well as the ceremony undertaken to finish the work all was done in prayer and reverence.

Pine Needle Turtle Basket

ca. 2000

Long Pine Needles, Twine

Consuela Richardson (Haliwa-Saponi)

North Carolina

Courtesy Schirra Gray (Piscataway) and Dorothy Gray (Rappahannock)

Using the common turtle motif in many Native North American cultures. In this region, tribal cosmologies teach that the Earth is a giant turtle. Frequently, North America is called Turtle Island.

Eastern Cherokee Basket

ca. 2018-2024

Honeysuckle Vine

Cherokee, North Carolina

On loan from Michael Nephew (Eastern Band Cherokee)

The basket is made of honeysuckle. It's part of a long tradition in the Eastern Band Cherokee that view basket making as a important and spiritual task. The persistent belief that baskets are living things, and that the creator of the basket imparts a fragment of their spirit into the basket, giving it the spark of life while also being a small extension of themselves.

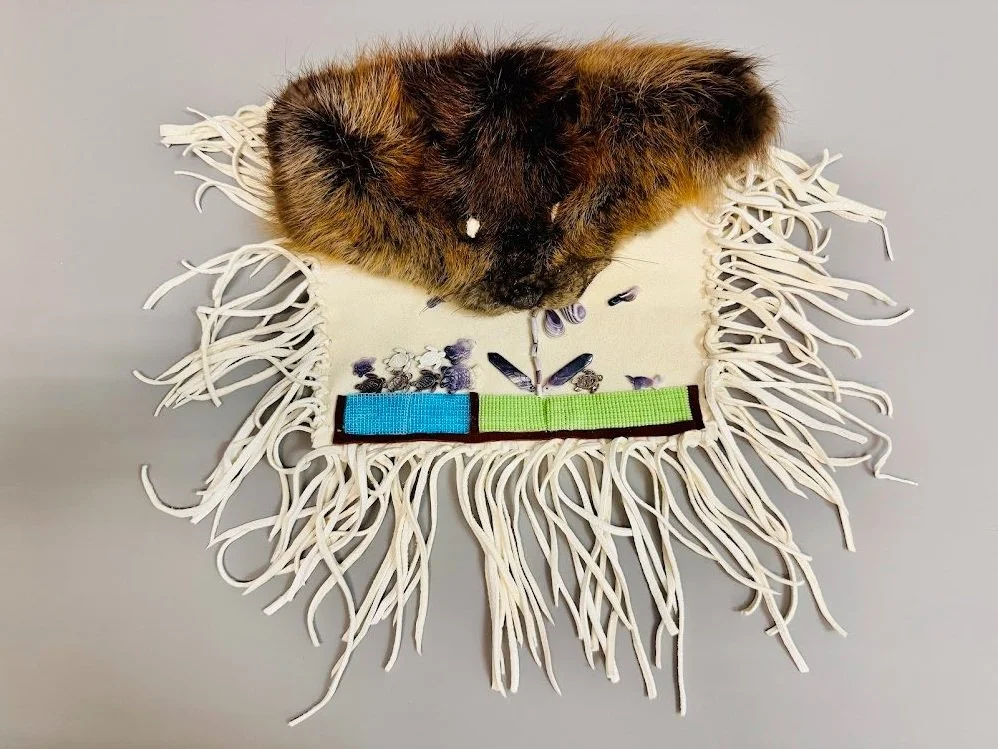

The Great Beaver, 2024

Hope S. Butler-Khodaei (Piscataway/Mapuche Pewenche)

beaver pelt, deer hide, wampum, glass beads, metal

This medicine bag represents Piscataway forests and river lands in harmony with living beings. The Great Beaver invokes the memory of the tayac , the Piscataway principal chief, Kittamaquund, and his clan lineage. His daughter, Mary Kittamaquund, and her English husband, Giles Brent, established homes on her ancestral lands in Northern Virginia. In 1653, Mary raised her family on Piscataway Neck, a place that would become River Farm - part of George Washington's Mount Vernon Estate. The Piscataway and Doeg peoples shared the Potomac River for centuries, their lands and lifeways intertwined.

Willakuti~Machaq Mara Andean New Year, 2024

Chakana Marcela Ardaya (Quechua/Guarani)

Canvas, wood, oil

A painting depicting four Andean people celebrating Willakuti-Machaq Mara, The Andean New Year with music, dancing, and weaving the Wiphala. The Wiphala is a pan Andean flag that is used to represent the Indigenous wisdom and principles of Pachakama (universal order) and Pachama (mother earth). They are all wearing traditional Andean dress and are surrounded by the mountains and Mama Quilla, who is the Quechua moon goddess.

Charango, 1984

Courtesy of Dr. Ricardo Sanchez (Quechua)

Armadillo, Wood, Metal, Wire

The Charango is an Andean instrument from the lute family that was created after Spanish Conquistadors introduced stringed instruments. Despite its past of colonization, the Charagno has long been a key part of traditional Andean music.

Piscataway Grindstone and Scraper

Circa 1600’s Stone

Mattawoman Creek, Marbury, Maryland

On loan from Schirra Gray (Piscataway) and Dorothy Gray (Rappahannock)

An ancestral Piscataway grindstone and pestle that was likely used to grind various seeds or for paints, vital parts of daily life.

Morral, 2024

Diego Velasquez (Maya Ixil)

Cotton Thread

Explore the vibrant spectrum of Ixil Tradition. Crafted with care by skilled artisan Diego Velasco Perez, this design is a celebration of cultural richness. From the vivid hues inspired by the rainbow to intricate animal motifs, including the majestic horse in the middle and graceful birds on both sides, each thread tells a story steeped in heritage. Passed down through generations, this exquisite piece honors the craftsmanship of Ixil women, weaving the straps together while retelling history and artistry. Experience the essence of tradition with every stitch.

Video Interview with Diego “Te’k” Velasco Perez (Maya Ixil)

Interviewer: Osvaldo Duran-Rojas

Videographer: Ben Bowen

Date recorded: April 2 2024

In this interview Diego “Te’k” Velasco Perez, discusses the aftermath of the Guatemalan Genocide, the cultural relevance of weaving to Mayan communities, the discrimination that Mayan people face daily, and how they maintain and grow their culture in spite of language barriers here in the DMV.

Quechua Hat, 2023

Originally from Peru

Alpaca Wool

On loan from Ozcollo Espinoza (Quechua, Coahuiltecan, Karankawa)

Alpaca wool has been used for clothing in the Andes for thousands of years. This is woven with Andean imagery and patterns, including that of an alpaca. Hats like theses have been worn to ward off the cold for generations and are still worn today.

Featured Poetry

Poema Para Awicha

Jair Carrasco (Aymara)

"Empieza en lago del sagrado, donde vivió por lo menos por un rato,

Aprendiendo de la tierra, iluminando la y las sierra,

Contandome la escena de cuando murio su mami, la belleza,

En sus manos de ahí cumpliera, la jornada de escaleras,

El trabajo lo llevó afuera, hasta la ciudad donde encontró la guerra,

Del Banzar en los setentas, pero asi ella cultivo la fuerza,

Dando vida a ella y su siembras, un hombre y tres hembras,

Negocios y cremalleras, diplomáticos de afuera,

Claro siempre hay mas que tu o ellos no supieran,

Llegó a los estados, dijo nomas por momento o un rato,

Para cuidar a la niña y los chamacos,

Pero había más hijos cada año,

Con cuñadas y cuñados,

Un tío ancestro del presente y el pasado,

La familia siguió migrando,

La awicha trabajando y dando platos,

El regalo que sigue regalando,

El pegamento y el guato,

Que nos puso más cercano,

Pero así ya pasan los años,

Y no todos se queda el mismo,

El caliente se vuelve frío,

Temporadas secas en el río,

Pero tu memoria awicha

Siempre estará

Conmigo ."

Poem for Grandmother

Jair Carrasco (Aymara)

"It begins in sacred lake, where she lived at least for a while,

Learning from the land, illuminating the mountains,

Telling me the scene when her mom died, the beautiful,

In her hands, she would begin the journey of ladders,

Work took her out to the city where she found war,

From Banzar in the seventies, but that's how she cultivated strength,

Giving life to her and her sowing, a man and three females,

Business of zippers, working for diplomats from outside,

Of course there is always more than you or they will know,

She came to the states, she said just for a moment or a while,

To take care of the little girl and the kids,

But there were more children every year,

With sisters-in-law and brother-in-law,

Ancestor uncles of the present and the past,

The family continued to migrate,

The Awicha working and providing dishes,

The gift that keeps on giving,

The glue and the knot,

That brought us closer,

Yet the years go by,

And not everything stays the same,

The hot turns cold,

Dry seasons in the river,

But your memory Awicha

Will always be

With me."

Poem by Geronimo Ramirez (Maya Ixil)

They came, they came like hyenas

They entered our home

They stained our altar

They invaded, they stole our Lands

They are like children of darkness

Wash your hands

They are called saviors

They proclaim themselves liberators

They came, they stripped my soul

They killed my father and mother

They killed my daughter

And they have exiled my grandchildren

In his colonial chair

They laugh, they mock and celebrate my nakedness

And they say in their hearts, we have done it

And we are lords of these lands

Oh widows and orphans

Take your rods

Let's go out to the streets

Let us offer our lives as an offering of struggle and justice so

that our grandchildren can recover what they have stolen

from us.

Ellos llegaron, llegaron como hienas

Entraron a nuestro hogar

Mancharon nuestro altar

Invadieron, robaron nuestras Tierras

Ellos son como hijos de la oscuridad

Se lavan las manos

Se llaman salvadores

Se proclaman libertadores

Llegaron, desnudaron mi alma

Mataron mi padre y madre

Mataron mi hija

Y han exiliado a mis nietos

En su silla colonial

Se ríen, se burlan y celebren mi desnudez

Y dicen en su corazón, lo hemos logrado

Y somos señores de estas Tierras

Oh viudas y huérfanos

Tomen sus varas

Salgamos a las calles

Ofrezcamos nuestra vida como ofrenda de lucha y justicia

para que nuestros nietos vuelvan a recuperar lo que nos

han robado.

Featured Artworks

Finding Our Rhythm: A Collaborative Sculpture, 2024

Girasol O’Neill

Scrapwood, air-drying clay, acrylic, found objects, wire

Finding Our Rhythm was designed for the Carter School's 2024 Conflict Resolution Youth Summit. The sculpture evokes the steady, cyclical, and grounding nature of resilience. Indigenous American folklore of celestial bodies, Turtle Island, and Jingle Dancers were the guides for the entire composition. The bodies of the Sun and Moon are locked in dance over Turtle Island, with his fan stirring the heavens as her fan stirs the seas. During the workshop, the students were tasked with piecing together the bodies without any blueprints before creating their decorations. Almost all materials were recycled/repurposed from George Mason’s Facilities Yard.

Girasol O’Neill is a multimedia artist, art teacher, and human rights activist based in the DC Metro area. He graduated from George Mason University in 2022 with a Bachelors of Fine Arts and currently works as an Elementary Arts teacher with Arlington Public Schools. O'Neill's work explores presence, emotional exchange, and socio-political themes through fusing symbols and vibrant colors in whimsical, surreal compositions.

CJ Davis is a Mexican American painter whose work is deeply rooted in healing, resilience, and identity. Born into a family of Indigenous Mexican ancestry, she channels her heritage and lived experiences into vibrant, expressive paintings that serve as both personal testimony and communal reflection. Based in Northern Virginia, CJ merges her background in public health policy with her passion for art, using creative expression as a tool for transformation and advocacy.

Her work is informed by her journey as a survivor of domestic violence. Through bold colors, ancestral symbolism, and deeply emotive storytelling, CJ’s paintings explore themes of generational trauma, reconnection, and the power of reclaiming one’s narrative.

Matriarch, 2023

CJ Davis

Oil

This is my great grandmother, Leonor. The name Leonor means light. I found this out after painting this portrait, but I found it fitting. My color palette was inspired by a spiritual ancestral connection. I am spiritual and I find it grounding to think of the generations before me. Indigenous to Mexico, my family carries on the traditions learned, including artisan crafting and cooking.

Abuela, 2023

CJ Davis

Oil

This is a portrait of my abuela. Her hands, pictured in the other painting, and her spirit have inspired me throughout my life to work with my hands, whether that be through our traditional artisan crafts such as embroidery, or cooking and community service. She taught me the importance of our culture, family, and resilience.

Mama, 2023

CJ Davis

Oil

This portrait of my mother means so much to me, as I consider her a light. She is a quiet and mighty force, with immense strength. I hope you are able to see that in her through this painting, and how much love she holds in her eyes and spirit.

Grounding (A Self Portrait), 2023

CJ Davis

Oil

This is one of my few painted self portraits of myself that have a toned down color scheme and more “human” flesh tones. This is significant to me in these 4 portraits I have of my great grandmother, grandmother, mother and I. The portrait of my great grandmother holds a spiritual, bright color palette, and the colors of each portrait become more “realistic" as it comes down through generations. I believe this contrast shows the spiritual realm from the past coming forward to the present human future.

Abuela’s Hands, 2023

CJ Davis

Acrylic

I took this picture of my abuela’s hands when she was making masa. I have bonded with her through cooking and carrying on the traditions of our recipes from Mexico. Corn and corn flour or maize is a staple in Mexican culture for cooking. Cooking together and eating the fruits of our labor is a strong communion point for us and the community we build around us, whether that has been in Mexico or here.

Xōchipilli, 2024

CJ Davis

Digital

The Aztec Deity of the Arts, associated with love, flowers, and painting. He is often associated with the maize God, Centeol. I find this connection fitting with myself, as a painter and have maize as such a staple in our family recipes and culture.

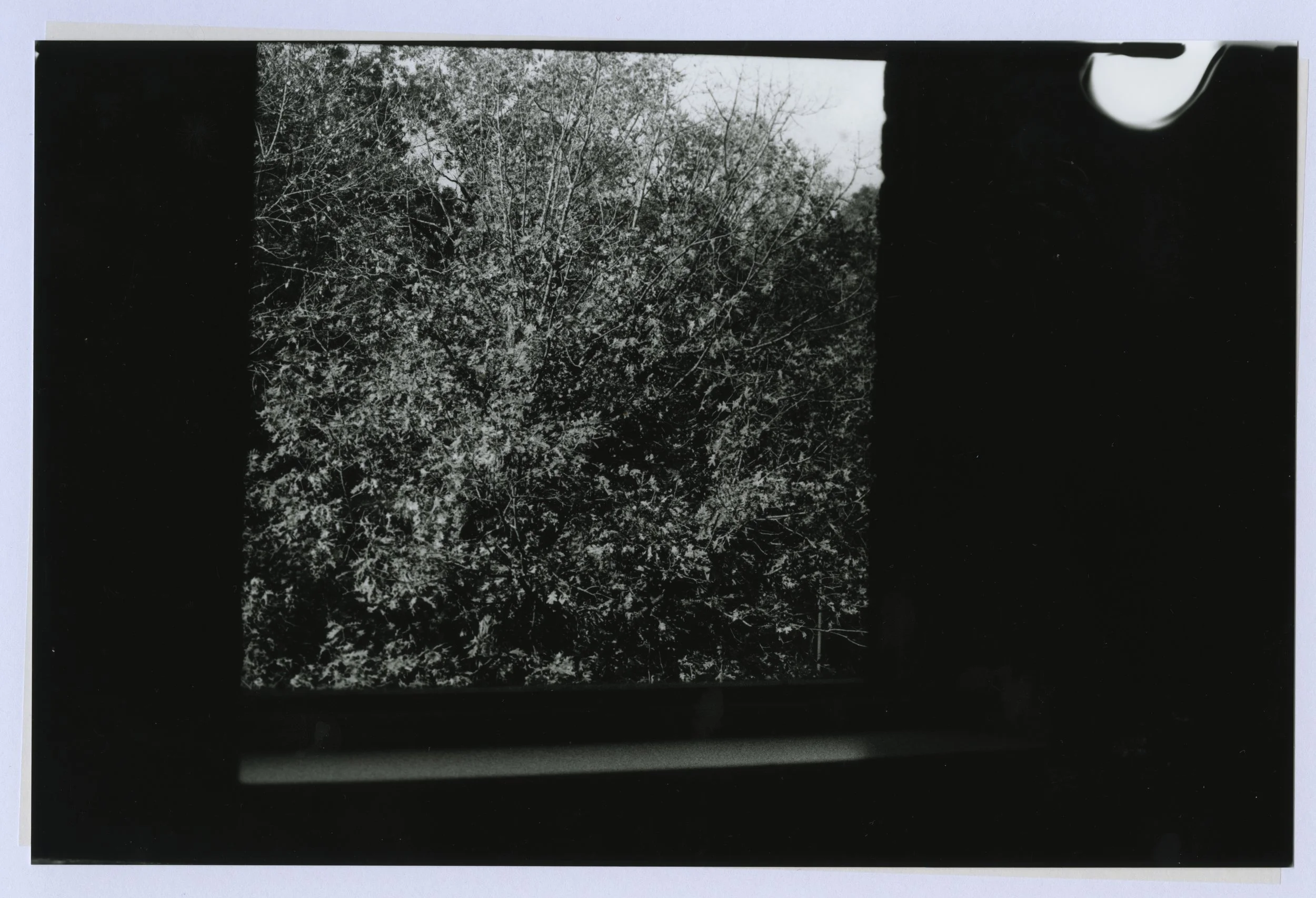

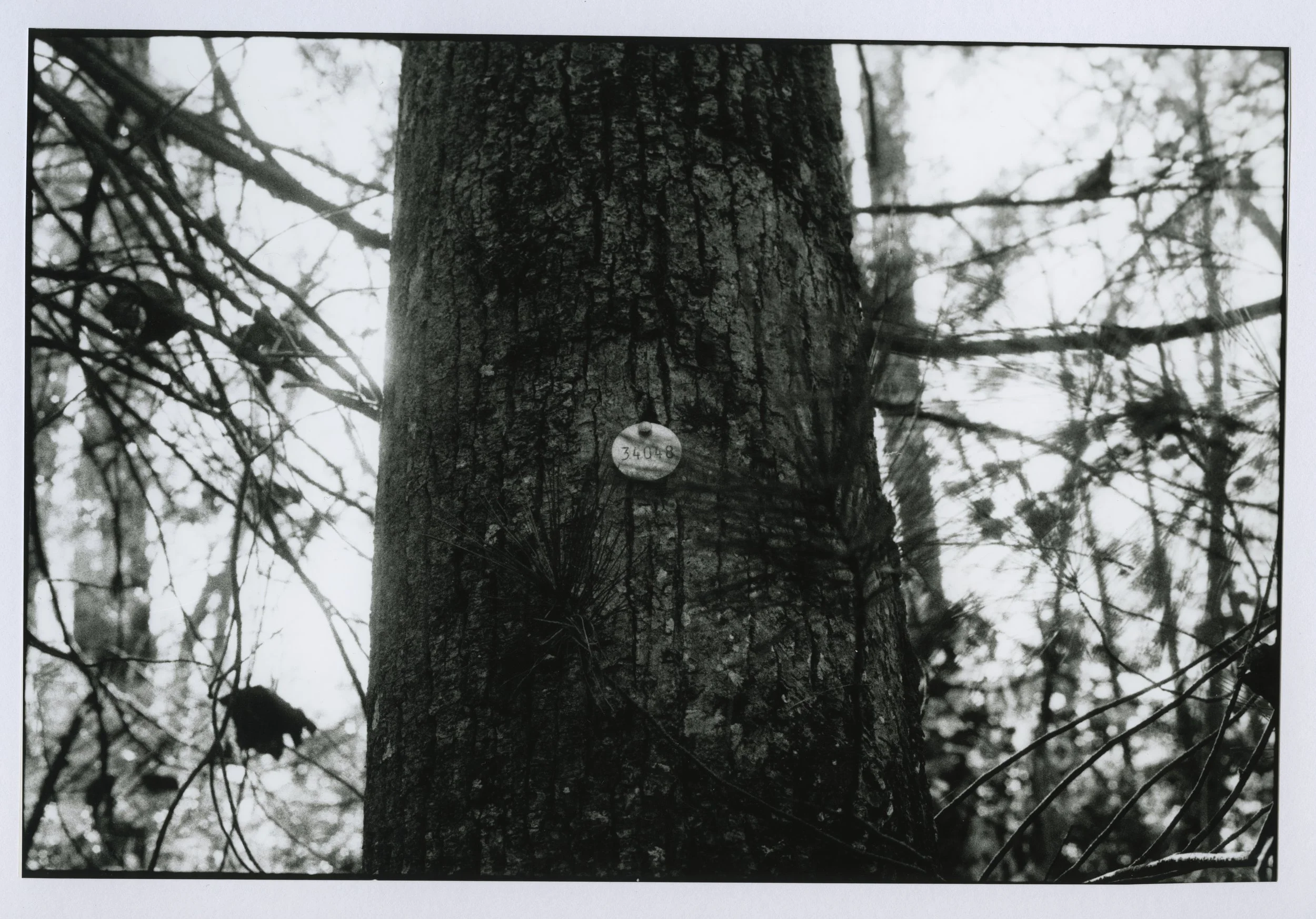

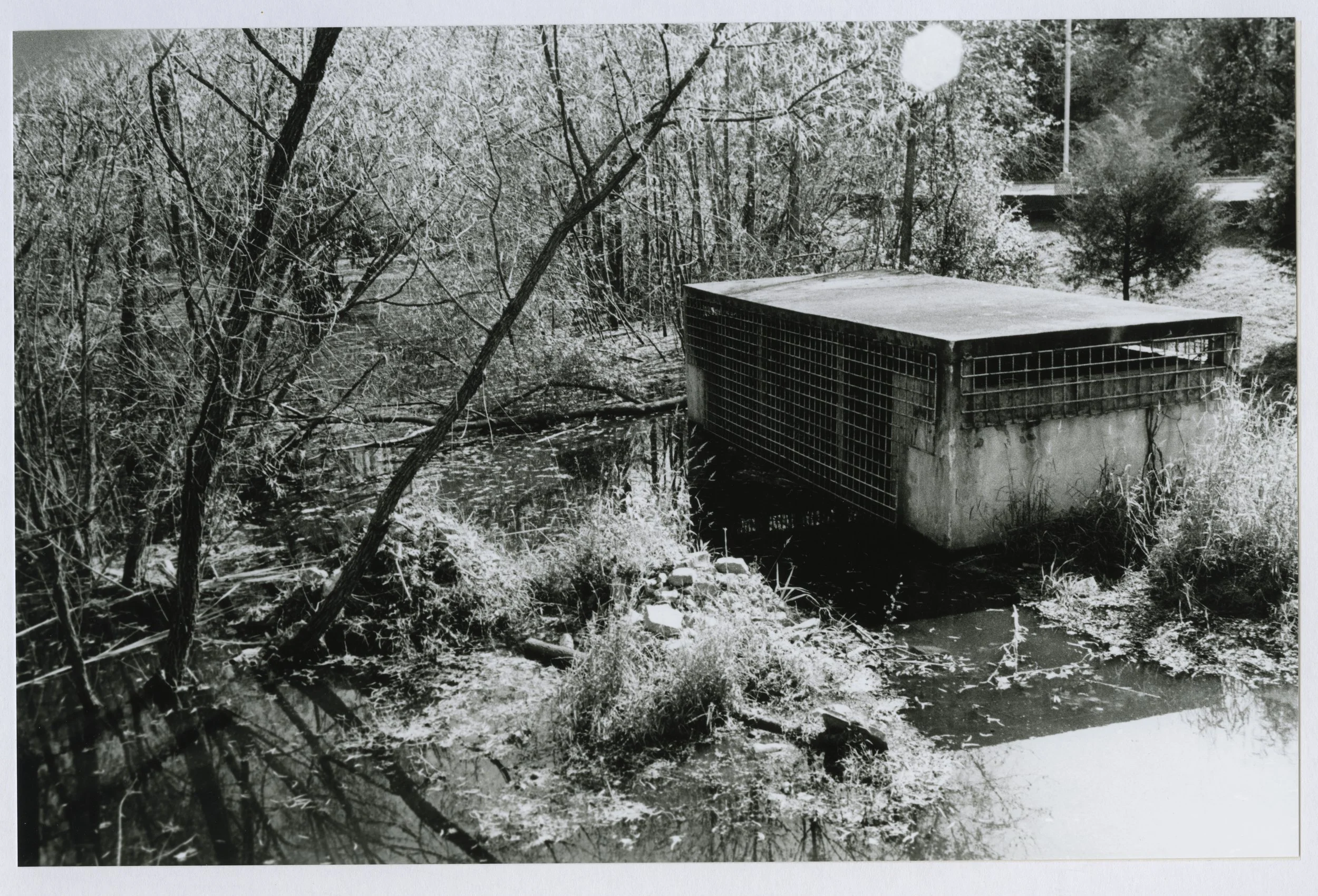

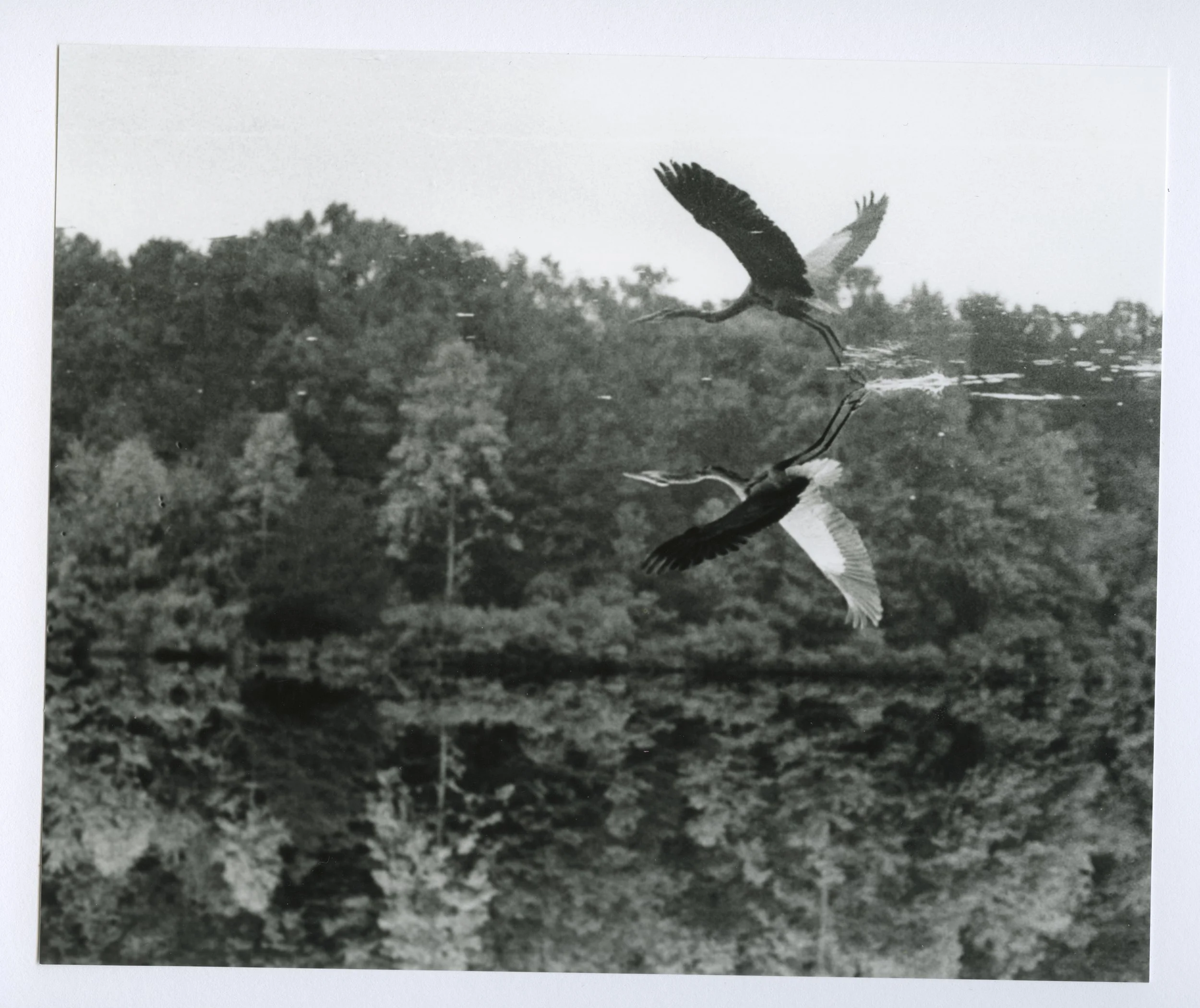

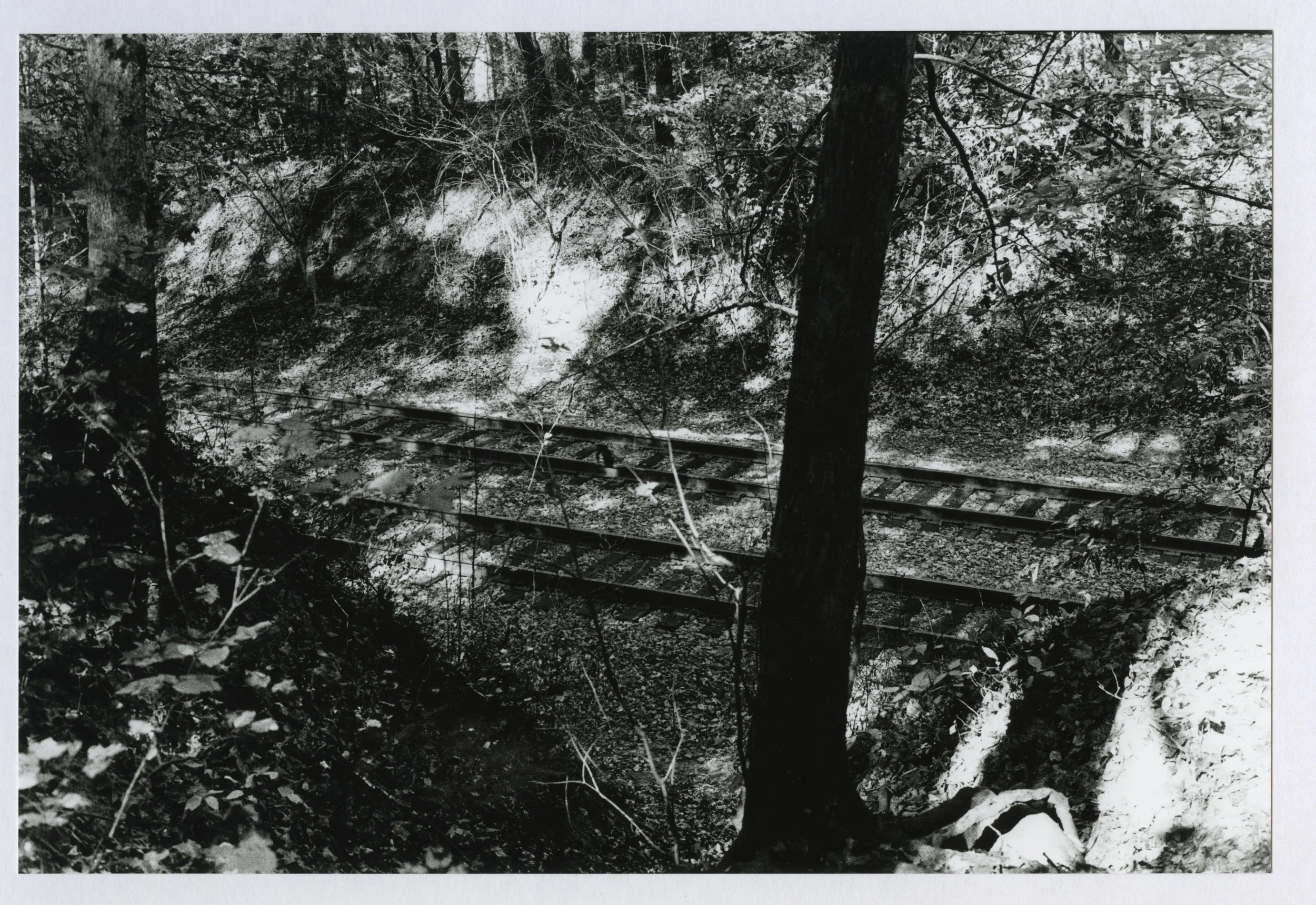

Select Black & White Photographs by Intro to Darkroom Students

During the fall 2024 semester, Professor Stephanie Benassi’s Intro to Darkroom students were invited to create photographs exploring the complex history of Native American land, specifically in Northern Virginia, including the George Mason University campus. The students’ photographs engage in a visual dialogue that connects the past with the present, providing a lens through which viewers can examine the land in the context of Indigenous history and perspectives.

As viewers engage with the images, they are encouraged to consider more than just the natural beauty of the land. They are urged to reflect on the deep historical layers that have shaped these spaces over time. The work sheds light on the often overlooked stories of Indigenous peoples whose lands were altered by colonization, displacement, and the erosion of cultural landscapes.

The students’ photographs include scenes of land that has been transformed for suburban development, now home to schools, gas stations, and fences that create boundaries, replacing slower-paced, communal systems of living. The students also captured scenes of commuter rail tracks and metro systems, which divide and fragment landscapes in ways that disrupt the land’s original flow and connectivity. Each photograph serves as a prompt, asking viewers to reconsider how urban development impacts Indigenous cultural landscapes and how history’s effects still echo in the present.

In contrast, some images depict intentional landscapes, such as food forests and composting sites, that show active efforts to nurture and restore these areas. These acts of restoration are not just ecological but cultural, offering pathways for healing, resistance, and reclamation of Indigenous spaces.

Ultimately, this body of work offers a nuanced perspective on landscape photography. It invites reflection on Native American history, the legacy of colonization, and the ongoing effort to reclaim and regenerate the land. Through these images, students offer a visual narrative that challenges conventional views of land ownership and usage, emphasizing the resilience of Indigenous peoples and their connection to the land.

Members of George Mason’s Native American and Indigenous Alliance

Formed nearly 20 years ago at Mason as a supportive community, the Native American Indigenous Alliance (NAIA) celebrates and educates about global tribal cultures, histories, and contemporary experiences.

They are the next generation. They are their ancestor's wildest dreams.

London Red Cloud Poor Thunder

Oglala Lakota

Livi Solis-Castillo

Lenca Quechua and Pipil

Desirae Suina

Cochiti Pueblo

Ozcollo Espinoza

Coahuiltecan, Karankawa, and Quechua

These four portraits were photographed by Ayman Rashid.

Ayman Rashid is a Graphic Design major and Photography minor in his senior year of university. His work primarily focuses on studio lighting in a variety of genres such as fashion, product photography, and more. He is also a photographer for George Mason University’s Office of University Branding, where he photographs for GMU’s primary media outlets. He is passionate about fashion design, architecture, and editorial photography, with influences such as Ann Demeulemeester, Jack Bridgeland, and Alexey Brodovitch. He aims to continue working as a freelance graphic designer and photographer out of college, and hopes to eventually work in the fashion industry.

www.aymanrashid.com

Exhibition Bookshelf

Indigeneity and Diaspora - Books in the Window Series at Provisions Library

Provisions Library is located in room L001 of the Art and Design Building on George Mason University’s Fairfax campus.

This book display explores the intersection of indigeneity and diaspora. Indigeneity is rooted in deep connections to land, community, and culture. Yet, paradoxically, it also carries the histories of displacement, forced migration, and survival in the face of colonialism and socio-economic hardships. For those who have been removed from their ancestral homelands, the struggle to revive connections and reclaim roots is ongoing. At the same time, those who have migrated from other Indigenous lands and settled in spaces with layered histories seek to maintain their own cultural ties while respecting the histories of the land they now inhabit. In this way, indigeneity and diaspora are intertwined. When land, history, and people are honored, these experiences can coexist, resisting forces that seek to sever those connections. This book display presents key perspectives on indigeneity and diaspora, offering a dynamic lens to understand the complexities of identity, belonging, and resilience.

Themes Explored in This Collection

Indigenous Identity & Survival – How Indigenous communities assert and sustain their identities amidst colonial histories, systemic erasure, and cultural transformations.

Resistance & Political Struggles – Movements for self-determination, constitutional recognition, and governance in the face of ongoing oppression and global exploitation.

Performance & Public Representation – The role of performance, art, and public space in shaping and contesting narratives of indigeneity, belonging, and sovereignty.

Museums, Heritage & Historical Narratives – Debates over representation, cultural ownership, and the responsibilities of institutions in preserving and interpreting Indigenous histories.

Migration, Displacement & Global Indigeneity – Indigenous experiences in urban spaces, diasporic communities, and the ongoing impacts of forced migration, colonization, and globalization.

Through this selection, we invite you to explore indigeneity and diaspora as dynamic, intersecting forces—stories of resilience, adaptation, and the enduring ties that connect people to land, culture, and each other.

BOOKS IN THE WINDOW AT PROVISIONS LIBRARY

On Display until March 31

Provisions Library, L001 Art and Design Building

BOOK COLLECTION

Louisiana Creole Peoplehood: Afro-Indigeneity and Community – Edited by Rain Prud'homme-Cranford, Darryl Barthé Jr., and Andrew Jolivétte (2022)

The Politics of Indigeneity: Challenging the State in Canada and Aotearoa New Zealand – Roger Maaka & Augie Fleras (2005)

Urban Mountain Beings: History, Indigeneity, and Geographies of Time in Quito, Ecuador – Kathleen S. Fine-Dare (2020)

Defiant Indigeneity: The Politics of Hawaiian Performance – Stephanie N. Teves (2018)

Performing Indigeneity: Global Histories and Contemporary Experiences – Edited by Laura R. Graham & H. Penny (2014)

Archaeologies of "Us" and "Them": Debating History, Heritage, and Indigeneity – Edited by Charlotta Hillerdal, Anna Karlström, & Carl-Gösta Ojala (2017)

500 Years of Indigenous Resistance Comic Book: Revised and Expanded – Gord Hill; Foreword by Pamela Palmater (2021)

Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto – Taiaiake Alfred (1999)

Paradigm Wars: Indigenous Peoples' Resistance to Globalization – Edited by Jerry Mander (2006)

Carl Beam: The Poetics of Being – Greg A. Hill, Carl Beam, & Gerald McMaster (2010)

Spirited Encounters: American Indians Protest Museum Policies and Practices – Karen Coody Cooper (2007)

Being Indigenous in Jim Crow Virginia: Powhatan People and the Color Line – Laura J. Feller (2022)

The readings below are available at George Mason Libraries, Provisions Library, or freely online.

Land Acknowledgement

At the place George Mason University occupies, we give greetings and thanksgivings to the recognized Virginia tribes who have lovingly stewarded these lands for millennia including the Rappahannock, Pamunkey, Upper Mattaponi, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Nansemond, Monacan, Mattaponi, Patawomeck, and Nottaway, past, present, and future; and to the Piscataway tribes, who have lived on both sides of the river from time immemorial. The education offered here is a credit to the land that has received our students. The good they will do in this world is the harvest of the soil upon which they stand, sit, and live.