AVEDON/BALDWIN: NOTHING PERSONAL

/UPCOMING EVENTS

NOTHING PERSONAL

A COLLABORATION IN BLACK AND WHITE

Mason Exhibitions Arlington

January 31 - May 3, 2025

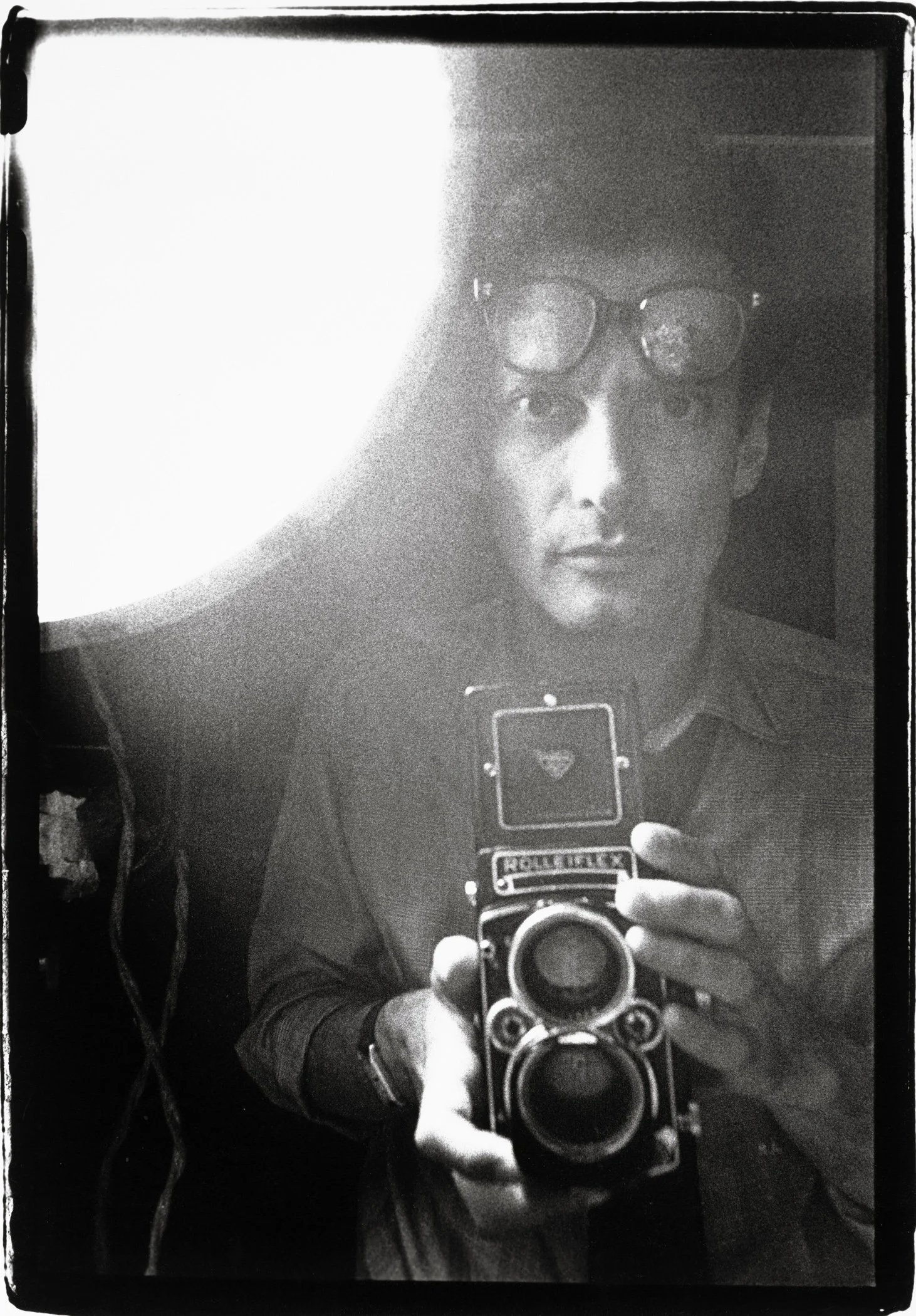

Baldwin and Avedon in Finland while working on Nothing Personal in 1964

This exhibition closely examines the book, Nothing Personal (1964), a collaborative artwork in book form by two legendary American artists, James Baldwin, the African American writer, public intellectual, and civil rights activist, and Richard Avedon the Jewish fashion and portrait photographer. Nothing Personal is a unique cultural object, presenting images of celebrity and the celebration of exceptionalism alongside depictions of the corrosive effects of capitalism and racism on society.

As we celebrate the 100th year since James Baldwin’s birth, and mark 60 years since the first publication of Nothing Personal, the book remains provocative. We continue to ask the same questions that Baldwin and Avedon were posing in 1964. We are still channel surfing or doom-scrolling; obsessing over appearances, while protests for systemic change continue. Global tensions and threats of nuclear war remain high. Wealth inequalities continue to escalate, and many people struggle to meet their basic needs, including mental health and housing.

Nothing Personal serves as a reminder of the power of art and literature to wield social change. As you engage with the exhibition, we encourage you to draw out the connections to current events, and consider how each of us can collaborate, like Baldwin and Avedon, in creating a vision for a more compassionate and just world.

Interested in scheduling a tour with the curators? Email Alissa Maru at amaru@gmu.edu

Channel surfing. To begin his essay for the book Nothing Personal, James Baldwin describes watching commercials on his black and white television. His unique command of language transforms this normally mundane and ubiquitous experience into a revelation of the American consumer subconscious and its addictions to surfaces, quick fixes, sexual gratification, and power.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Nothing Personal was first published in November 1964 by Atheneum Publishers and Penguin Books priced at $12.95, equivalent to $130 today. A paperback edition was released the following year in April by Dell Publishing, costing $1.50. In 2017, the book was reissued by Taschen Books and is now out-of-print, commanding up to $1,200 as a rare book.

Nothing Personal is a large-format, slipcased book containing a four-part essay written expressly for the book by Baldwin and fifty-four photographic portraits made by Avedon taken between 1954 and 1964. The book’s radical design was conceived by Marvin Israel, the influential art director at Harper’s Bazaar, the leading fashion magazine of the time, where Avedon was his close colleague and collaborator.

INSTALLATION VIEWS

EXHIBITION TOUR WITH DON RUSSELL

ABOUT JAMES BALDWIN

James Baldwin (1924-1987) was an influential African American writer, essayist, playwright, and social critic whose works addressed complex issues of race, sexuality, and identity in America. Baldwin's early experiences in a racially segregated and economically disadvantaged community profoundly shaped his worldview and literary voice. His involvement with other artists in the United States and abroad played a significant role in shaping his career and amplifying his social and political messages.

Family History and Early Life

James Baldwin was born on August 2, 1924, in Harlem, New York City. His mother, Emma Berdis Jones, left his biological father due to his drug abuse and married David Baldwin, a preacher who adopted James. David Baldwin, the son of an enslaved woman, moved from New Orleans to the North in the early 1920s. Struggling during the Great Depression, he provided for his family as best as he could, but his "intolerable bitterness of spirit" stemmed from his internalized racism and inability to see his own worth. This bitterness led to his eventual commitment to a mental institution in 1943, where he died of tuberculosis.

Baldwin's mother, originally from Deal Island, Maryland, moved to New York in the early 1920s seeking a better life. She married David Baldwin when James was two years old. Baldwin grew up in poverty with a strict religious upbringing and a deep connection to his mother and siblings. He faced significant challenges, including losing several friends to suicide and experiencing his own struggles with mental health, attempting suicide multiple times.

Education and Influences

James Baldwin began school in 1929 at P.S. 124, where his talent for writing was quickly recognized. Encouraged by his teachers, Baldwin frequented the public library and won praise for his early work, including a song praised by Mayor La Guardia. In 1934, at P.S. 24, his white teacher Orilla Miller nurtured his brilliance, introducing him to plays, movies, and museums. However, their relationship faded in 1939 when Baldwin began preaching at the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly and distanced himself from "ungodly" activities.

At Frederick Douglass Junior High, Baldwin was influenced by African American teachers Countee Cullen and Herman Porter, who introduced him to the school’s literary club and made him editor-in-chief of the school magazine. During this time, Baldwin grappled with his identity, struggling with sexual and religious awakenings. Assaulted by a male stranger, he sought refuge in religion, though questions of race and sexuality continued to haunt him.

In 1938, Baldwin was accepted into DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, where he connected with mostly Jewish peers and contributed to the school’s literary magazine, The Magpie, forming a lifelong friendship with Richard Avedon. Baldwin’s high school and preaching careers ended as World War II began. Facing racism and the threat of being drafted, he moved to Paris, France, where he found the freedom to explore his views on race and sexuality, becoming part of a vibrant expatriate community, including novelist Richard Wright and painter Beauford Delaney.

ABOUT RICHARD AVEDON

Richard Avedon was an influential Jewish-American photographer whose fashion and portraiture work emerged during the post-World War II era in New York City. Avedon’s groundbreaking approach to fashion imagery made him a dramatic interpreter and arbiter of taste and sophistication. He was driven to transgress the borderline between commerce and art, engaging in the social and political movements of his time, particularly the Civil Rights Movement and Anti-War Movement. Wielding a humanistic lens, he challenged popular standards of beauty and illuminated the iconic faces of politicians, celebrities, intellectuals, activists, and workers of the time. Despite lifelong insecurity about his Jewish heritage and his queer identity, he found tremendous commercial success and notoriety, attributable as much to his photographic vision as to the force of his personality.

Family History and Early Life

Richard Avedon was born on May 15, 1923, in New York City, to Jacob Israel Avedon, a Russian-Jewish immigrant who ran a successful retail dress business on 5th Avenue, and Anna Avedon from a family of dress designers. His sister Louise, who was an early subject and muse of Avedon’s, increasingly suffered from mental illness and was subsequently institutionalized. Avedon attended DeWitt Clinton High School from 1937-1940 in the Bronx, where he collaborated on the school's literary magazine, The Magpie, with his fellow student, James Baldwin.

His friendship with James Baldwin played a significant role in shaping his perspectives. Avedon provided material support to members of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee through photographic workshops and donations of cameras and film to document their struggles.

Education and Early Career

Avedon did not graduate high school probably due to an undiagnosed learning disability. Instead, he and a photographer friend joined the U.S. Merchant Marine Photographic Section during World War II, where Avedon produced thousands of identification photos of sailors. Following his service, he studied photography with Alexey Brodovitch, then art director of Harper's Bazaar, the leading fashion magazine. Avedon’s portraits can be viewed as a creative reaction and counterpoint to his fashion photography and they are instantly recognizable for their starkness and psychological depth. Avedon’s signature seamless white backgrounds heighten his subjects in an atomic flash rendering human shadows etched onto the surface of the page.

Avedon quit Harper’s Bazaar in 1965 after editorial and creative differences stemming from the inclusion of too many people of color in the famous April issue for which Avedon was art director. Vogue magazine soon hired him and he went on to produce numerous cover images, feature stories, and advertisements for the magazine between 1965 and 1988. Later he became the first staff photographer for the New Yorker, until he died.

BALDWIN AND AVEDON

Baldwin and Avedon were high school friends who discovered mutual interests while working together on the school’s literary magazine in 1941. Their relationship continued over the years as they each found their way into the intellectual and cultural elites of midcentury New York City. Both experienced acute social prejudice, Avedon for being Jewish and Baldwin for being black. While Baldwin embraced his homosexuality as a teenager, Avedon married several times and had a child, while also being actively, but not publicly, bisexual. Both abandoned their religious beliefs and embraced humanism and egalitarianism. Neither attended university but both gained profound acclaim for their creative contributions.

MAKING THE EXHIBITION

Two copies of the 1964 edition have been disassembled (unbound) and its original pages have been mounted in sequence on the gallery walls. These original pages were printed by rotogravure, an intaglio printing process where the image is etched onto the surface of a metal plate, holding ink that is pressed onto the paper’s surface. The process is renowned for rendering a very wide range of image tonality on the printed page. In addition, a selection of images and texts from the book have been enlarged and printed directly onto the gallery walls using innovative vertical wall printing technology. A graphic chronological timeline of the 1960s has been curated within the exhibition, connecting the flow of ideas, themes, and events to those in the book.

BALDWIN AND AVEDON: FRIENDSHIP AND BLACK-JEWISH COLLABORATION

BY DR. LANITRA BERGER

Nothing Personal: A Collaboration in Black and White is an opportunity to learn more about the groundbreaking collaboration between James Baldwin and Richard Avedon. Equally as critical, it is also a chance to reflect on the Black-Jewish relationship through this unlikely friendship between a Black writer and a Jewish photographer who met in 1930s New York City.

Although Baldwin and Avedon’s Nothing Personal publication is a social commentary on American life in the 1960s with a focus on race relations, the book’s honest and direct approach emerged from their close relationship, which began when they were teenagers living in a mixed-race working-class Bronx neighborhood. They met as students at the integrated DeWitt Clinton High School where they both worked on the school’s literary magazine, The Magpie. Despite living in close proximity, New York neighborhoods were still divided by race and ethnicity, with Blacks and Jews concentrated in different areas. Yet, Baldwin and Avedon still found ways to spend time together after school, crossing racial lines to get to know each other as human beings and aspiring creatives. Meanwhile, Dewitt Clinton High School brought students different backgrounds into the classroom and produced many famous Black and Jewish graduates who went on to make significant contributions to American culture and life, including artist Charles Alston, poet Countee Cullen, comic book publisher Stan Lee, and fashion designer Ralph Lauren. Baldwin and Avedon were undoubtedly influenced by being immersed in this multicultural learning environment.

Both artists illuminated the challenges of navigating identity in mid-century America, but what’s equally as interesting is how their artistic and literary interventions transcended racial boundaries. Avedon, who was raised in a Jewish family that embraced social justice values, was committed to photographing fashion models of color, outraging executives at Harper’s Bazaar magazine and ultimately leading to his departure for Vogue. His working relationship with Black model Donyale Luna elevated Avedon’s status as the preeminent photographic eye for fashion and implored the industry to dismantle white femininity as the standard of beauty. Baldwin, whose social conscience was shaped by the brutality of slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and homophobia, wrote extensively about race relations in America. By the early 1960s, he had established himself as one of America’s preeminent social critics and essayists through his volumes Notes of a Native Son (1955) and The Fire Next Time (1963). Informed by his personal relationships with Jewish friends, including Avedon, and his keen observations of Blacks and Jews in Harlem and other New York neighborhoods, Baldwin’s analysis of Black-Jewish interactions added new layers of complexity to an oftentimes confounding relationship. In his 1967 New York Times essay, “Negroes are antisemitic because they are antiwhite,” Baldwin argued that Jews’ tenuous relationship to white identity—never white enough by white supremacist standards—would continue to cause strife between Blacks and Jews when they should be working together. “A genuinely candid confrontation between Negroes and American Jews would prove of inestimable value,” he wrote, noting that “What is really at question is whether Americans already have an identity or are still sufficiently flexible to achieve one.” Leaving the door open for dialogue and opening the potential for creating mutual understanding, Baldwin’s essay was prescient when it was published and continues to be a provocative invitation to dialogue.

Sixty years after its publication, Baldwin and Avedon’s Nothing Personal is an example of why the Black-Jewish relationship matters and why it’s more necessary today. Even when there is disagreement or the alliance is strained, there are still opportunities to drive social change through authentic personal connections. Scholars often describe the Civil Rights Movement and the mid-twentieth century as the peak moment for Black-Jewish collaborations in politics and culture. They point to examples such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. marching arm in arm for racial justice with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and children’s book author Ezra Jack Keats’ book, The Snowy Day, the first American children’s book to feature a Black child as the main character, as evidence of cross-cultural and interfaith relationships that produced meaningful social change. Although these relationships are crucial to our understanding of the power of Black-Jewish partnerships in transforming American society, Baldwin and Avedon’s Nothing Personal goes further by enabling us to peer into a friendship and understand how two people connected across difference to find common purpose by holding a mirror up to American society and inviting us look at our own reflection. Baldwin’s last words in his essay are an evocative statement on both friendship and the Black-Jewish relationship: “The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out.”

CONTRIBUTORS

CURATORS

Donald Russell - GMU Curator of Collections & Director, Mason Exhibitions

Yassmin Salem - Programs Manager, Mason Exhibitions

EXHIBITION DESIGN

Rick Heffner - Assistant Professor, GMU School of Art

Jeffrey Kenney - Associate Curator, Mason Exhibitions, Abdulrahman Naanseh - Gallery Assistant, Mason Exhibitions, Steven Luu - Documentarian, Amani Jefferson - Video Montage Editor

Vertical Wall Printing by InkElementDC

RESEARCH

Dr. LaNitra Berger - Associate Professor of Art History & Director of African and African American Studies at GMU

Diana Guzijan - Art Amplifier Research Fellow, Provisions Library

Soojung Paek - Graduate Professional Assistant, Provisions Library

Greg Kuchmek - Chronology Research & Graphic Design Consultant

Stephanie Grimm, Art and Art History Librarian, University Libraries

Jen Fehsenfeld, English and Philosophy Librarian, University Libraries

William Barker - Research Intern

Justin Alexander Rogers - Research Intern

SPECIAL THANKS

Leeya Mehta -Director of Alan Cheuse International Writers Center

Annie Chen and Alix Nyden - SOA Print technicians

Ben Ashworth - GMU School of Art Sculpture Supervisor

Andrew Jorgenson - Technical Manager, GMU Film and Video Studies

Barry Broadway - Broadway Galleries

Vaughn from eBay who sold us the refurbished vintage television

BALDWIN100

This exhibition appears in conjunction with the Baldwin100, a celebration of the centenary of Baldwin's birth. It is a collaborative arts, scholarship and cultural project encompassing a year-long series of initiatives from February 2024-February 2025, designed to convene a wider Washington area audience to engage deeply with James Baldwin’s work. Organized by the Alan Cheuse International Writers Center and the many partners on the Baldwin100 Planning Committee.

Listen to a podcast with Dr. Keith Clark: James Baldwin’s insights on American life and identity with President Gregory Washington

On this episode of Access to Excellence, Distinguished University Professor Keith Clark, professor of English and African and African American studies in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, joins President Gregory Washington to discuss the literary journey of James Baldwin and his reflections on his life of courage and wisdom as he studied the human experience.